Four critically endangered vulture species have returned to the Liwonde National Park in Malawi, after having not been seen there for more than 20 years. The birds’ resurgence is credited to the successful reintroduction of cheetahs and lions, as the predators’ prey remains increase food availability for vultures.

In 2017, seven cheetahs were relocated to Liwonde by African Parks, a conservation group working in collaboration with Malawi’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW). Vultures emerged within days, even though the big cats remained confined to their acclimatization boma.

The cheetah translocation project has been a huge success. The population within the 548,000-hectare (1.3 million-acre) park recently reached 42, and a second generation of cheetahs are also now breeding and raising cubs.

Vultures, cheetahs and lions vanished from Liwonde and other protected areas because of a poaching crisis that ravaged the area in the 1990s and early 2000s. One severe consequence of the vultures being wiped out was that animals who died of natural causes were not picked clean by the birds, who rapidly consume carcasses and the potentially deadly diseases they carry.

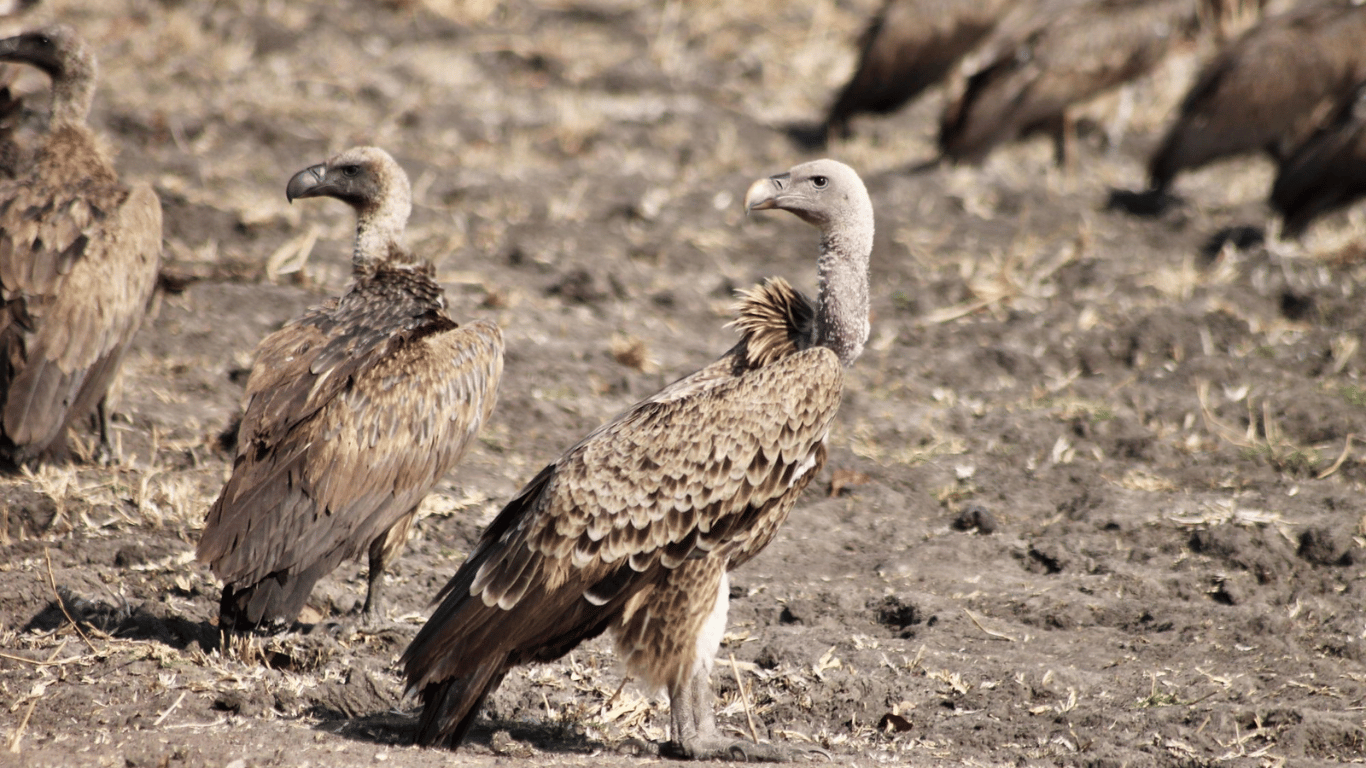

While there was an emergence of scavengers that wouldn’t normally be seen in parks with thriving ecosystems, they were not nearly as efficient as vultures. Other birds of prey such as bateleur and tawny fish eagles, marabou storks and ospreys that would usually be overpowered by vultures soon became the predominant scavengers in the area.

Effective management of the park by African Parks and the DNPW has played a crucial role in the return of the vultures. “It’s very encouraging to have vultures come back to Liwonde,” said ecologist Tiwonge Mzumara-Gawa of the Malawi University of Science and Technology.

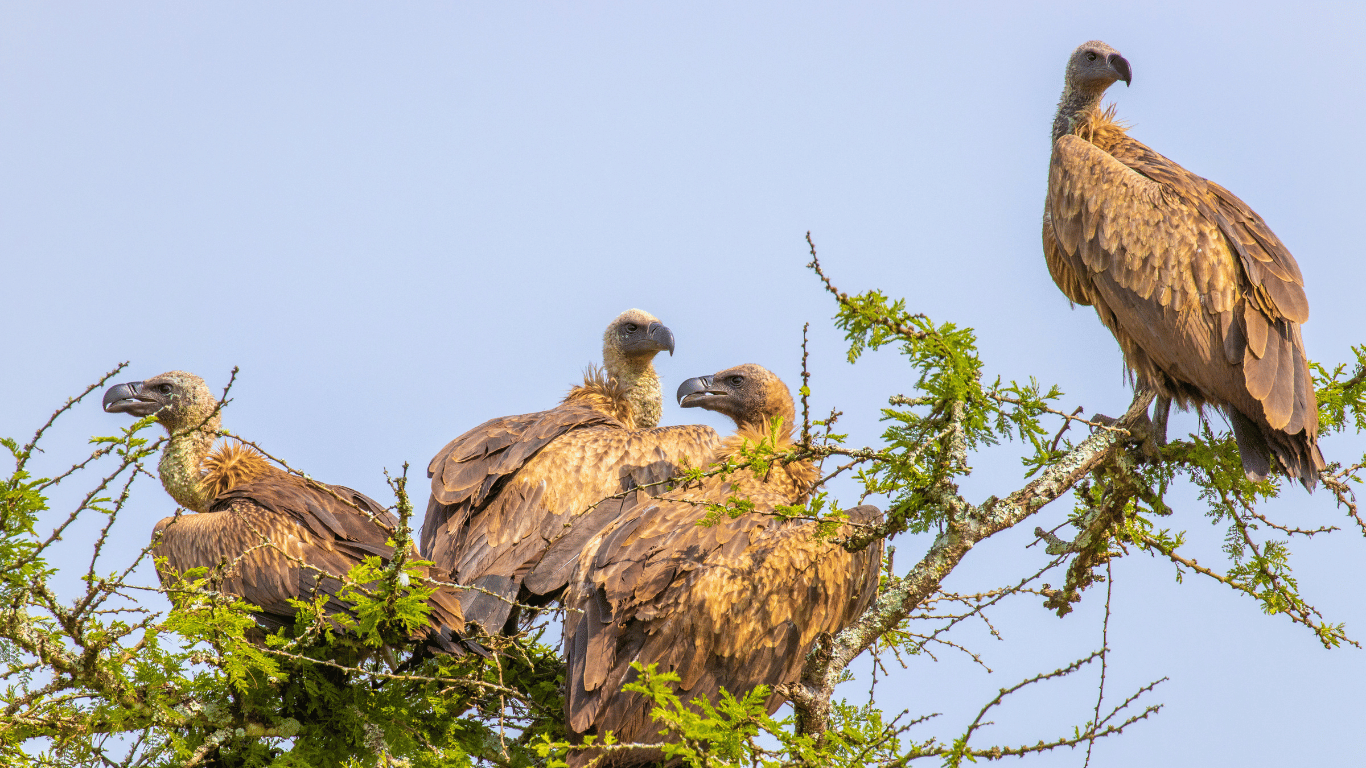

The first two to arrive back in 2017 were critically endangered white-backed and hooded vultures. Three other species have since been recorded in Liwonde: critically endangered white-headed and Ruppell’s vultures, and lappet-faced vultures. Another major victory in 2021 was the discovery of three white-backed vulture nests. These are the first active breeding records of vultures in Liwonde after more than two decades.

Positive news regarding African vultures is hard to come by. A report published in the scientific journal Conservation Letters in 2015 revealed that seven species of African vulture declined by more than 80% over three generations. Poisoning and habitat loss have drastically diminished their numbers.

Poison is frequently used to hunt and kill Africa’s wildlife. It is mostly used against predators like lions, hyenas and jackals as revenge for attacks on farmers’ livestock. Unfortunately, vultures are often the unintentional or deliberate victims. By carefully tracking Malawi’s vulture population, the impact of poisoning can be reduced. Once a vulture with a mortality sensor dies, people on the ground are alerted and can rapidly respond to poisoning incidents.

The insatiable demand for charcoal has also stripped much of Malawi’s landscape. “With the recovery of the vultures we need to protect the large trees that they like to nest in,” says Mzumara-Gawa. Lengwe and the Majete Wildlife Reserve are vital to Liwonde’s new vulture population. Data gathered from tagging white-backed vultures in Liwonde in 2021 revealed that the birds are migrating between all three protected areas.

“For Malawi’s small breeding population of vultures, protected areas are crucial safe havens for the birds, the prey that they feed on as well as for cheetahs and lions,” says David Barritt, Executive Director of Animal Survival International.

“Poisoning and habitat destruction continue to threaten the survival of vultures in Malawi. But better park management and meticulous monitoring efforts offer a renewed sense of hope for vultures and other wildlife.”

Image credits: Image 2 OliviaSievert_OryxTheJournal, Image 3: OliviaSievert_LilongweWildlifeTrust