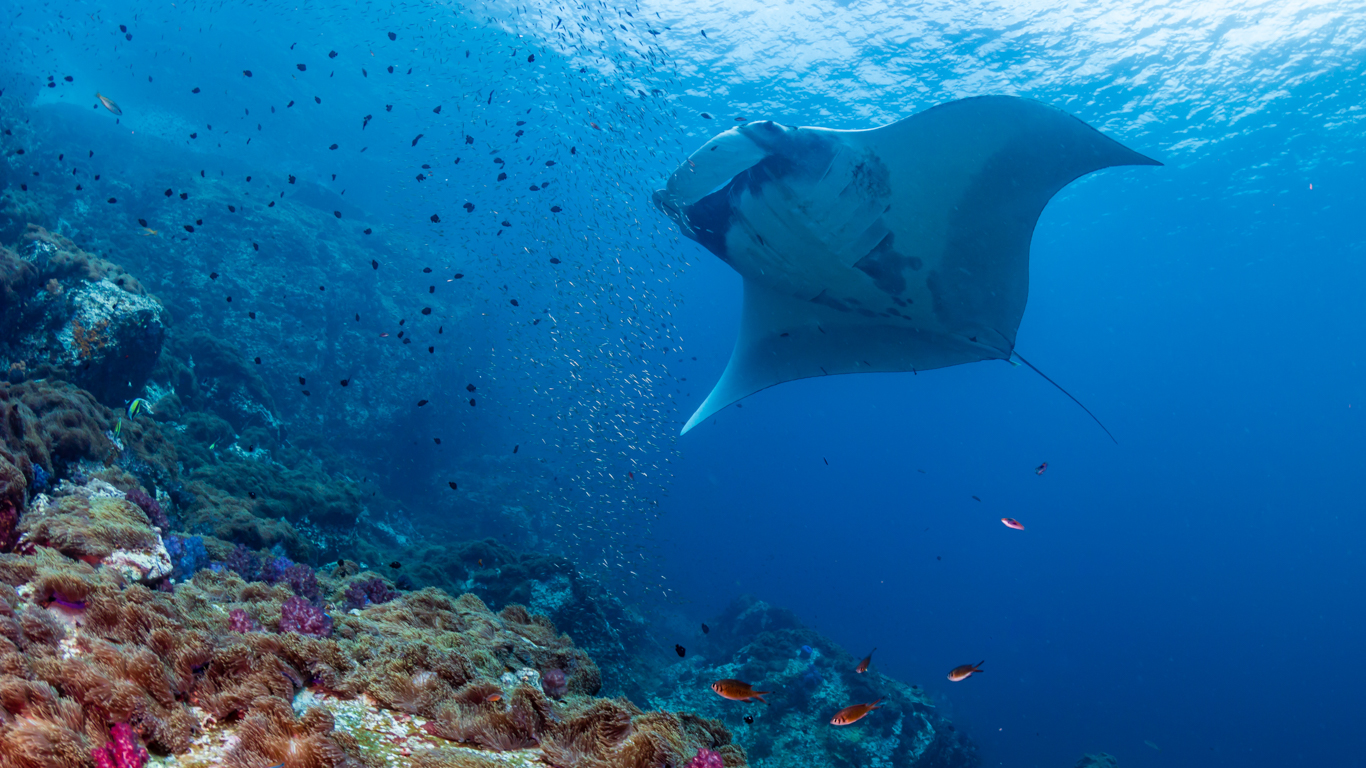

More than half of the world’s known species of coral reef sharks and rays are now threatened with extinction, reports conservation news service Mongabay. The primary culprit? Overfishing, along with the ravages of climate change and other environmental threats.

According to a study published in Nature Communications journal earlier this month, populations of 94 species of coral reef shark and rays are declining, with rays at greater risk. The study identified 79 of the world’s 134 coral reef-associated ray and shark species – known as chondrichthyans – as being in one of the threatened categories on the IUCN Red List – a comprehensive inventory on the conservation status of the planet’s fauna and flora.

The study showed that overfishing appeared to be the greatest cause for the population decline, followed by climate change, habitat loss and degradation, urban and commercial development, and pollution.

Reef sharks and rays are often caught for human consumption, and in some cases for their body parts, which are used to make apparel or accessories. Others are caught for aquariums, for feed for domestic animals, and for “traditional medicines.”

“There are few policies that have been put in place to manage reef sharks and rays,” said lead author Samantha Sherman of Simon Fraser University in Canada.

“These species are difficult to manage as they occur mainly in countries with very high coastal populations that rely on resources from the ocean for food and earning money to support their families,” she added. “These countries also tend to have large numbers of small boats and small markets spread throughout the coast, which makes implementation of any policies difficult.”

The authors of the study developed a Red List Index to track progress toward international biodiversity targets over the past half century. They found 14 species fit the “critically endangered” category, making them nearly extinct in the wild; 24 species were “endangered,” which indicates population reduction of 50 to 70% in the past three generations, and 41 species were classed as “vulnerable” as their populations had declined by around 20 to 50% in the past three generations.

“There are many interesting facts about sharks and rays, but I would like to highlight stingrays, as people don’t hear about them often,” Sherman said. “Stingrays act as ecosystem engineers because when they feed, they create pits in the sand called ‘feeding pits.’ When the tide goes out, some pits will hold water and provide a place for small fish and other animals to hide from bigger predators.”

The study identified the coral reefs of Southeast Asia and northern Australia and as having the strongest population of both sharks and rays. It also found that sharks faced the most threat in the western Atlantic, while rays were most vulnerable across Asia and southeast Africa. Areas like the Pacific islands, where reef sharks and rays are fairly abundant, could serve as refuges for threatened species, making them key to regional and global conservation efforts.

The risk of extinction is greatest for widely distributed large species, such as the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) and reef manta ray (Mobula alfredi). Both are found in the waters of more than 60 countries. The study further found that risk is also particularly high in countries with higher fishing pressure and weaker governance, such as Brazil, Tanzania and Indonesia.

Effective ways to help combat this worrying decline would be through improved control and management across all scales of fisheries, combined with strong enforcement and effective marine protected areas at regional and global levels of government. In addition, better education and diversification of rural livelihoods in regions with overexploited reefs could help reduce fishing pressure on threatened species.

“Lots of reef species occur in many countries, meaning conservation efforts require global cooperation,” Sherman said, adding that international trade regulations for sharks and rays that are meant to protect them still lack effective implementation and thus fall short in tackling the problem of bycatch-related deaths.

Mongabay said that without large scale action to improve the status of reef sharks and rays, their populations will continue to decline with increasingly dire consequences for the ecosystem health of coral reefs and coastal communities whose livelihoods depend on them.

“The findings are being communicated by all the co-authors and others that work in the field to relevant governments they already work with to make the case for greater action to conserve these species,” Sherman said.

Already, governmental failure to address these threats can be seen in many reefs around the world where shark populations have declined to steeply, they can be considered “functionally extinct” from these ecosystems. Sharks are apex predators which prey on sick and weak fish, leaving the stronger ones to reproduce. This helps maintain a healthy marine ecosystem.

“Human greed, apathy and ignorance are wiping out populations of both land and marine animals at a truly alarming rate,” said David Barritt, executive director of Animal Survival International (ASI). “Governments must urgently recognize that protecting ocean species is critical to the health of not only our marine ecosystems, but our planet as a whole. If we destroy our oceans and their inhabitants, we destroy our entire planet.”