Article written by Kiley Price

Originally published by Inside Climate News (Jun 21, 2024)

It’s taking poachers longer to find rhinos now that populations have dropped, researchers say.

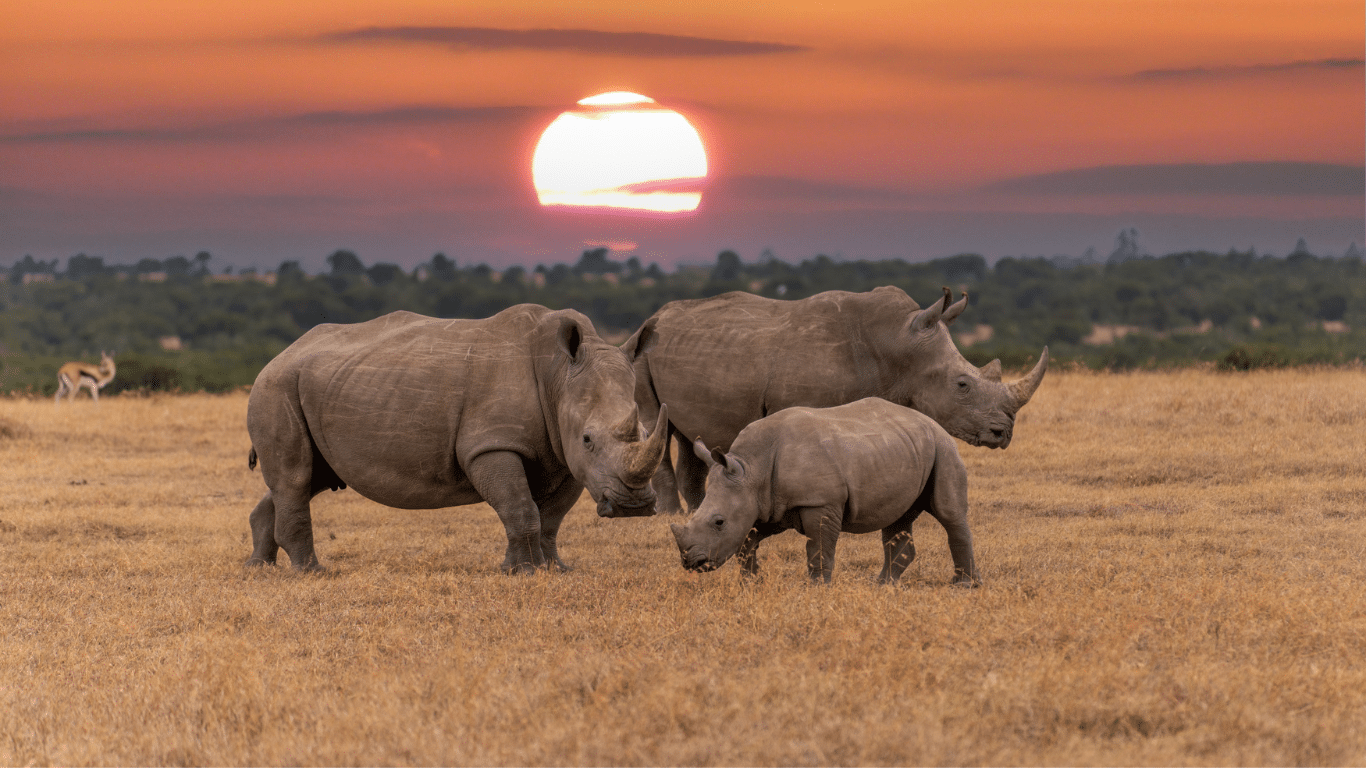

In recent years, the South African government has touted the steady decline of rhino poaching in Kruger National Park, the largest wildlife sanctuary in the country and a habitat for many of these iconic horned mammals.

But a new study, published Friday in Science Advances, suggests there may be more to this story. Using mathematical models, researchers found that the drop in poaching incidents could be due to an unfortunate fact: fewer rhinos.

Low population density makes poaching harder because rhinos are simply more difficult to track down, the researchers found. But the demand for rhino horns on the illegal wildlife market remains persistently high, and so has overall poaching activity in Kruger, the research concludes, despite anti-poaching measures. Climate change, meanwhile, could cause further havoc.

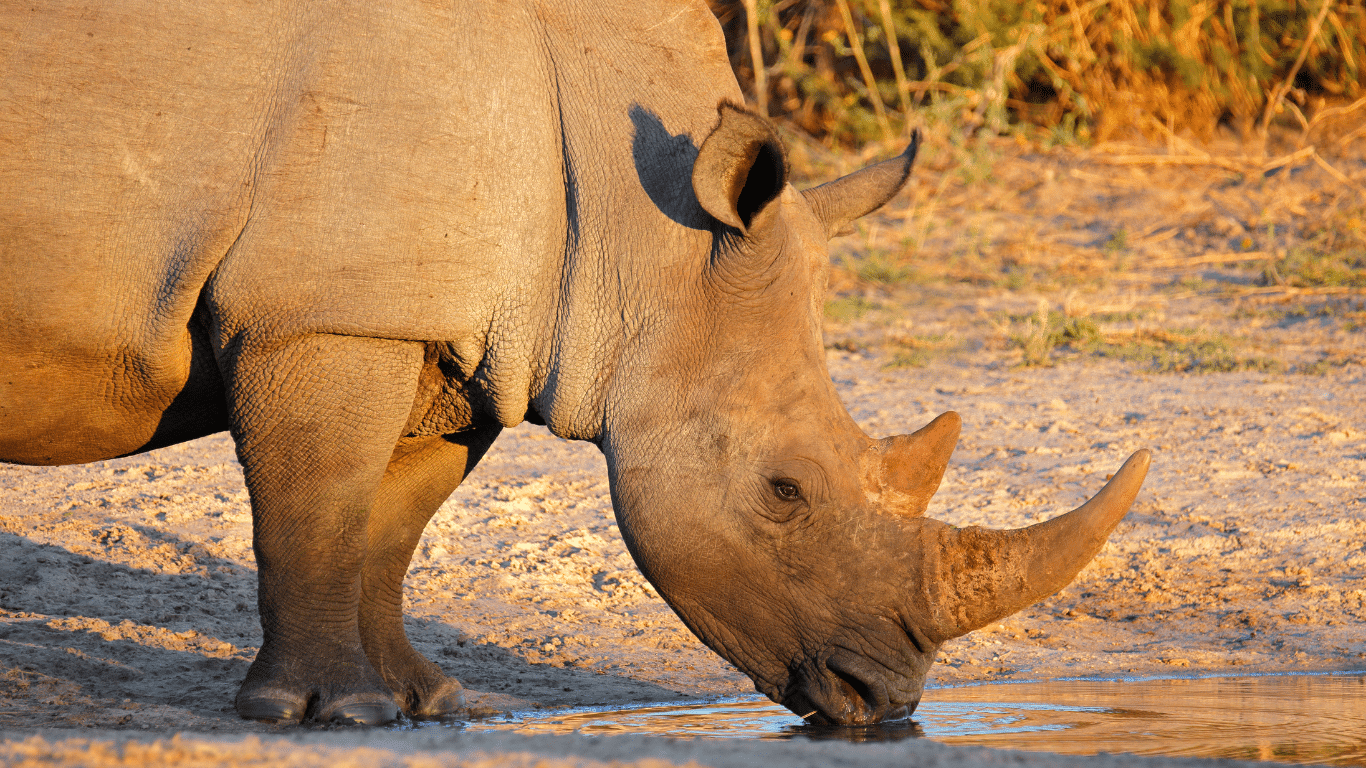

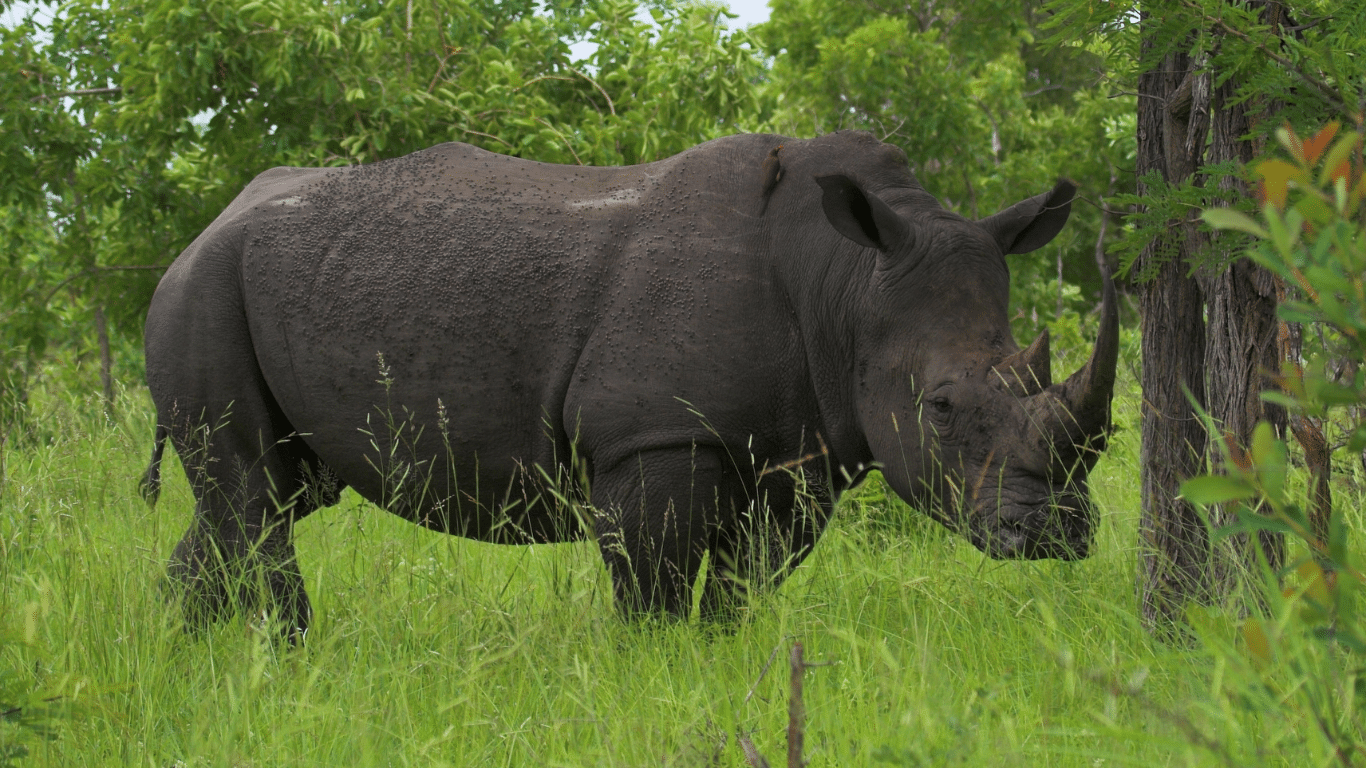

The poaching problem: White and black rhinos are among the largest land-based animals on Earth. Male white rhinos can measure 12 feet long and clock in at around 5,000 pounds (2,265kg, or 2.5 tons) as adults. But Kruger National Park covers 2 million hectares of land—about the same size as Israel. With only around 10,000 white rhinos left in all of South Africa, finding these hoofed ungulates in the park is harder than one might think.

Poachers often spend days searching for a rhino to kill for its horn, according to the study’s lead author, Jasper Eikelboom.

“There’s no way that poachers can find almost all the rhinos and kill them... because it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find them,” Eikelboom, an ecologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, told me.

This is why poachers aren’t giving up: A rhino horn—made of keratin, similar to human fingernails—can sell for $40,000 (around £31,545) or more on the illegal black market. Most of the demand comes from Southeast Asia and China, where some people buy rhino horns as a status symbol or use them in traditional medicines.

“Searching for a couple of days or a couple of weeks is still worth it because there’s an enormous profit margin,” Eikelboom said. Over the past few decades, the South African government has implemented a range of strategies to combat this illegal activity, from pairing ranger teams with dog patrol units to dehorning rhinos in Kruger.

While South Africa has seen a modest decrease in rhino poaching incidents across Kruger in recent years, Eikelboom and his co-author, Herbert Prins, another ecologist at Wageningen University, wanted to determine if part of the reason for the decline was the smaller pool of animals to hunt. To do this, they used a model that calculated how far poachers moved on average from 2007 to 2022 to find a rhino in the context of the dwindling rhino densities.

Their data reveals that poaching activity has proportionally remained consistent as rhino populations have dipped, despite the more stringent anti-poaching measures.

“We have to look at the relative numbers, like how many rhinos are being killed on a percentage basis instead of an absolute number,” Eikelboom said.

The research shows that anti-poaching efforts have not been strong enough to prevent population decline, the authors say, because illegal hunting activity should have gone down no matter what.

“It’s a fantastic first step in trying to quantify the issue and then setting up hypotheses for others to test,” said Dave Balfour, an independent conservation ecologist who wasn’t involved in the study. Balfour chairs the African Rhino Specialist Group of the nonprofit International Union for Conservation of Nature’s African Species Survival Commission. “Conserving rhinos in an area the size of Kruger, which is huge, is ideal for every purpose except the security needs of the species, and that’s because it’s just extremely difficult to secure an area that size.”

However, Balfour sees limitations in some of the paper’s assumptions. Its model follows the premise that many poachers are searching for rhinos without much information about where to look and that these “naive” poachers have to travel an average distance before stumbling upon one.

“I’m not sure that there is such a thing as a naive poacher. Just about every poaching incident relies on some form of internal-collaboration corruption,” Balfour said. “So how naive these poachers are is highly questionable, and whether the rhinos are broadly, evenly spread through the landscape, as I read in the paper, is also questionable.”

Risks from all sides: Rhino conservation is an exceedingly complex issue in South Africa. Many of the communities surrounding Kruger and other rhino habitats are impoverished, and unemployment rates in the country surpass 30 percent. Experts say these conditions are often the reason that individuals might risk dangerous wildlife encounters or a 25-year jail sentence to track down rhino horns. While poaching incidents have decreased in Kruger, they increased in the country overall last year, with 499 rhinos killed—51 more than in 2022, the BBC reports.

Rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall due to climate change could soon compound the problem, according to a study published in January. Rhino skin has very few sweat glands. That makes the animals particularly vulnerable to heat because they cannot cool off on a hot day by sweating like humans can. Instead, they must consume a lot of water or seek out shade to prevent heat stress. But the study found that climate change will likely push rhinos to the upper heat threshold that they can handle and require them to travel greater distances to access watering holes.

“Wildlife, and even humans, have to actually travel farther and farther to find water, and that means that... the risk of poaching, the risk of habitat destruction, or other types of interactions, will start to increase,” study author Timothy Randhir, an ecologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, told me.

He and the other authors say that the South African government could plant more trees and add watering holes to the landscape to help minimize these interactions and provide cooling spaces for the rhinos. However, the poaching issue is not going to be easy to solve. As the South African government continues to invest in anti-poaching measures, poachers are creating innovative strategies to get around them, reports Bloomberg.

In the long term, Eikelboom and co-authors of the poaching study write, reducing the demand for rhino horn will allow these mammals to “safely roam the wide African savannas again.” In the meantime, they say that smaller and more well-monitored “safe havens” for wildlife beyond Kruger will be crucial.